Efficiency vs. Readability

26 Sep 2019

Efficient code ≠ Good code

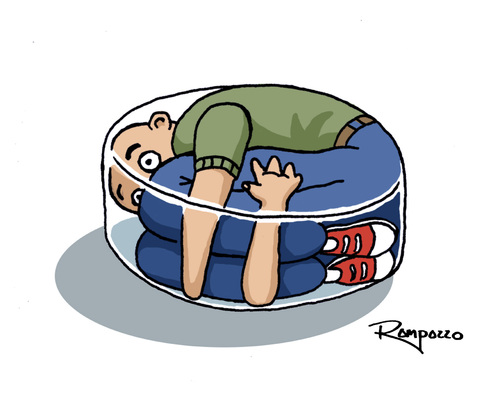

When I think of coding standards, I am reminded of my high school geometry notes. With the shorthand I had developed, geometric proofs that used to take up to 10 lines of notebook paper would take up no more than 1 line in my notes. Taking notes in that class became a sort of game, to see how much information I could cram onto one piece of paper. As I could read my tiny handwriting and decipher the symbols, it worked just fine for me. However, classmates who wanted to look at my notes weren’t so happy. Even though I may have saved a tree or two in my efforts to conserve paper, others in my class were unable to understand my notes and as a result collaboration and our mutual success suffered. Nowadays, compressing code into as few lines as possible doesn’t really save trees or electricity, and I’ve run out of excuses to format my writings so compactly. Just like that guy stuffed into a suitcase, at a certain point you start to question what’s so great about being efficient with space and begin to wish you had a little more room to spread out and function better.

We read what we write

I’ve read thousands of books throughout my life, and I’ve been able to achieve such a number for a few reasons. First, I learned to read English in school–spelling, grammar, punctuation…the works. Second, I learned how to understand words and phrases I didn’t understand–at first with a dictionary or contextual clues, and later with Google searches. Third, and most important, was that each of those books was written in the same language, with the same formatting rules and definitions for each string of characters. I was able to learn amazing things and experience fantastic stories simply because I was accustomed to their standards, language and otherwise. Simply put, we expect what we read to have certain rules and standards to make it easily readable, so it only makes sense that we would want anything we write to be just as easily read by others. By using the same standards, it is vastly easier to communicate with others and share ideas, which is especially important if we are looking for feedback to improve code.

Letting ESLint be my co-writer

Within the last week I have begun to use ESLint to help meet coding standards, and it’s been…interesting. As far as helping me discover coding errors and formatting oversights, it’s been a godsend. I can’t imagine how much time using ESLint (or something similar) will save me over the years–no longer having to hunt down missing semicolons or additional brackets. In addition, it even helps point out probable problems with my logic and algorithms, such that I can easily identify and fix errors before I even get the associated compiling error. Seeing that green checkmark signifying ESLint’s approval gives me just a little extra comfort when I finish my code, and it’s so nice. Sure, it may not give the expected output, but I know that if I have that little green checkmark the proofreading and editing won’t be so bad. Just as it’s helpful to have a passenger assist you when driving in an unfamiliar city or a park ranger guiding you in a forest, it’s entirely possible to find the path yourself but it’s much easier and quicker with the guidance.

Part Human, Part Machine

So here we are, writing code on a computer that will be compiled on computers and run on computers. It follows that a computer would help us generate code that its’ buddies will be reading in their language. Sure, I can write code that works, and with enough proofreading I can be somewhat sure it’s formatted correctly, but what’s the point? By focusing on the part our computers can’t do (yet) and allowing the computer to fix and check our code (not unlike spellcheck in a word processor) we can deliver a better product in less time. In our time-constrained culture where information is increasingly valuable, it doesn’t get much better than producing higher quality code in minimum time. Maybe someday ESLint will display warnings on my smart glasses that my shoes are untied or my fly is down…one can only hope!